October 2016 / A Ferocious Intimacy: Poetry by Grieving Mothers

ART, RESEARCH, THEORY: In the October column we are pleased to publish work by Nancy Gerber on the topic of maternal bereavement and introduce you to the work of poets Chanel Brenner and Alexis Rhone Fancher. (Biographies included at the end of this article.)

Nancy Gerber received her doctorate in English from Rutgers University and taught as a visiting lecturer for eight years in the English and Women’s Studies departments of Rutgers-Newark. Her books are Portrait of the Mother-Artist: Class and Creativity in Contemporary American Fiction (Lexington, 2003); Losing a Life: A Daughter’s Memoir of Caregiving (Hamilton, 2005); and Fire and Ice: Poetry and Prose (Arseya, 2014), a finalist for a Gradiva Award in poetry from the National Association for the Advancement of Psychoanalysis. She is currently an advanced candidate in psychoanalytic training at the Academy of Clinical and Applied Psychoanalysis.

A version of this essay appeared on line in Journal of Mother Studies, Issue 1. Gratitude to the editors, Kandee Kosior and Rosalind Howell, for permission to reprint this work.

A FEROCIOUS INTIMACY: POETRY BY GRIEVING MOTHERS

My interest in poetry by grieving mothers was born from the desire to learn about maternal bereavement. Two women I knew lost children in sudden, horrific accidents. How does a mother live with such profound loss? How is this loss experienced on the page? As a literary scholar and mother whose life has been shaped by motherhood and the written word, I found myself thinking about the death of a child and the relationship between mothers, grief, and the writing of poetry.

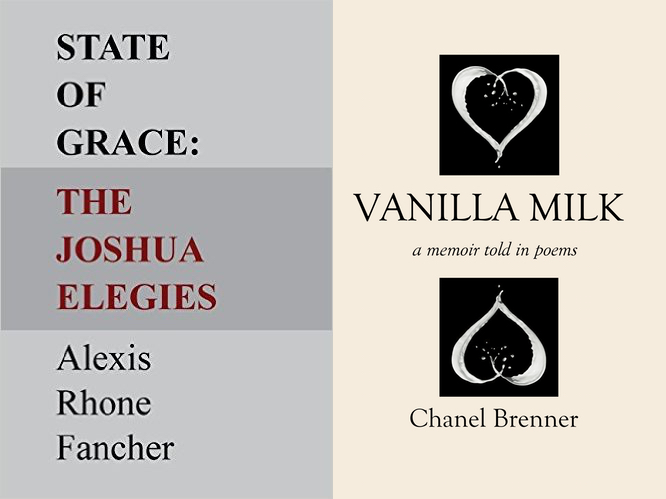

I learned about Chanel Brenner’s Vanilla Milk and Alexis Rhone Fancher’s State of Grace: The Joshua Elegies through the Internet. Vanilla Milk was listed for review on Mom Egg Review. I reviewed it and discovered Alexis Rhone Fancher’s State of Grace through Les Femmes Folles. It was a surprise to find, given the randomness of the Internet, that Brenner and Rhone Fancher are friends and writing partners who read and support each other’s work; Brenner wrote the foreword to Rhone Fancher’s book; Rhone Fancher dedicated her book to her son and to Brenner’s. Their partnership and friendship seemed to me to embody feminist collaboration and community at its best.

My interest in the topic involves a series of questions. What do bereaved mothers experience after the death of a child? What images and metaphors resonate in poems by grieving mothers? What do feminist scholars say about maternal bereavement? What is the relationship between writing poetry and mothers’ grief? My work is intended as one approach to the subject of poetry written by grieving mothers. In any case, read these poets. Their work will take your breath away. The poems say so much about life, loss, love, hope, despair, survival, and pain. Their words are the text, my remarks simply commentary.

Chanel Brenner and Alexis Rhone Fancher are mother-poets who write about a child’s death. The courageous act of Brenner’s son Riley died at the age of six from an AVM (arteriovenous malformation), whose existence was not known until it suddenly burst in his brain. Alexis Rhone Fancher’s son Joshua died at the age of twenty-six from cancer. In the preface to Vanilla Milk, Brenner writes that after Riley’s death, poems poured out of her. Instead of crying, she wrote poems. Rhone Fancher, who had written and published many poems before her son’s death, told me that after she wrote 'Over It', “it was like a spigot was opened and poems just kept coming out, over a few years.”

It’s interesting that both poets speak of water, an image associated with birth and the laboring mother’s body -- the poem as the mother’s tears, the writing as the birth of the mother’s grief, the bleeding of words on the page a reminder that mothers are deeply intimate with beginnings and endings. As Alicia Ostriker noted, “ . . . motherhood puts [the woman artist] in immediate and inescapable contact with life, death, beauty, growth, corruption” (130).

The death of the mother’s child brings the mother-poet face to face with the finiteness and fragility of existence in a culture where such issues are silenced and taboo. Moreover, when children die before their parents, parents undergo a painful reversal of expectations, a feeling of disorder and a perception that the course of life has been reversed: parents do not expect to bury their children. This theme is addressed in Brenner’s poem, 'Out of Order.' Riley’s younger brother Desmond sits in the car with his mother and father. He points to a cemetery and yells, “I want to go there!” His father replies, “You will someday” (57). Shocking and undeniable, the father’s reply reminds us: everyone dies, your brother died, one day you will die. No candy-coated platitudes can bury this truth.

In poems by grieving mothers, readers bear witness to the terrible knowledge that death, like life, does not mete out portions according to standards of justice or comprehensibility. In “The Give Away,” Brenner writes, “Nothing belongs to us, not our hair, not our thoughts, / not our sons” (38). Our bodies, which seem real and solid, material and weighty, are so much more fragile than we care to know or admit. Accidents or illness can destroy us, wreck our lives in the course of minutes or over prolonged years of suffering. Our bodies are not built to last; “a washing machine outlives a little boy,” Brenner reminds us (38). In Rhone Fancher’s poem, “Snow Globe,” the frozenness of time is explored. The speaker says: “Despair arrived, disguised as / nine pounds of ashes in a / velvet bag. . . . Better he’d arrived / as a snow globe, / a small figure, / standing alone at the bottom of his / cut short beauty. . . .” (29). The image of the snow globe is a metaphor for the frozenness of time: the child trapped inside a time bubble, his future truncated, his life cut short before he can live it. In “Mahogany Funeral Urn,” the speaker yearns for a movie she can fast forward or rewind in order to alter the sequence of time so she can “make him stick around” (31). She casts herself as a film director who yearns to script a different ending to the story even as she understands the impossibility of her wish.

Grief is described alternatively as fullness and emptiness in images that speak to the fullness of pregnancy and the emptying out of the mother’s body during labor. A mother’s grief is an embodied grief, a grief that lives in the body. In Brenner’s poem “Out of Body,” the speaker stares at the gutted fish on her luncheon plate. She understands she is that gutted fish – emptied, flayed – her guts, her womb ripped open. (40). Rhone Fancher describes the sense of being emptied by death in “when her son is dead seven years.” The speaker says: “a woman is dancing on the moon, / . . . / her feet are cooking. / her arms are empty . . . she thinks there is someone to feed . . . a woman is dancing on a cake plate / in her kitchen. / . . . skates to the bone-white middle” (43). The mother’s arms are empty, there is no one to feed, the plate is barren. But there is also fullness, in the waxing and waning of the moon, the ancient symbol of women’s fertility. The speaker regards the pregnant moon with “her big belly, / . . . lighting the way” (44). Is the speaker learning to balance the darkness of grief and the light of survival? The theme of grief as the insatiable hunger of emptiness appears in Brenner’s litany, “I Want” – “I want, I want, I want, I want –“ (39). The mother’s role is to feed her child, first with milk, then with love. What happens to the mother’s desire to love when that child is gone?

In mapping the terrain of maternal bereavement, feminist scholars note that the parental bond does not end with the child’s death (Bennett, 47). Bennett says, “The death of a child results in a journey for a mother, both with their child through an enduring relationship and without their child physically present to hold” (47). Space and time acquire different meanings for the bereaved mother, who, through imagination, ritual, prayer, dreams, or poetry maintains a connection to the dead child (Bennett 47, Hendrick, 38). Still, grief remains.

The poems by Alexis Rhone Fancher and Chanel Brenner are offerings of ferocious intimacy – ferocious in their pain and anger, in their exploration of love and longing. Intimacy is established by the poets’ openness to voicing and sharing their experiences and feelings in language at once carefully crafted and emotionally accessible. We might wish to turn away to protect ourselves from the ache and the longing, but we do so at our peril, for to do so is to isolate ourselves from what is human and fragile in all of us.

SPEAKING WITH CHANEL BRENNER AND ALEXIS RHONE FANCHER

Author’s note: The two poets were interviewed on separate occasions for this essay and did not hear each other’s responses. I have put their words in dialogue with each other because such a format reflects their collaborative relationship as friends and writing partners. Both have received awards: Vanilla Milk, the Eric Hoffer Award; Alexis Rhone Fancher has been nominated for three Pushcart Prizes and four Best of the Net awards. The interview with Chanel Brenner was conducted via cellphone on February 27, 2016; the interview with Alexis Rhone Fancher was conducted via cellphone on February 29, 2016.

NG: How did your book come into being?

CB: I started taking writing classes when Riley was two. I had always wanted to write, and I started taking classes with Jack Grapes. At that point I was mostly writing prose. The night Riley died I started writing poems. I had written a few poems prior to that, but that’s when I started to write a lot of poems. They just started coming out of me, one after another. About a year after he died, I started looking at all the poems and the story they told.

I was reading other poets at the time who had gone through loss, and I was inspired by the art they created. There was one book by Shelly Wagner called The Andrew Poems, about her son who drowned. It was one of the first books I read after Riley died. It was painful but I felt very connected to her, and I realized how much less alone I felt by connecting with other people who had been through something similar to me. I ended up carrying my journal everywhere after Riley died. I would take Desmond to his toddler class. It was at the same school Riley attended. There were a lot of moms who knew about what happened to him, and kids would come up to me and ask me about his whereabouts. I had all these moments that would happen, and I would just sit during the toddler class and write and go to my car and write. It was a way to document what was happening. I didn’t want to cry, I wanted to witness it, to make some kind of sense of it.

AF: My son died in September of 2007, and I didn’t really write much about it or him until the beginning of 2008, when I started studying with Jack Grapes, a famous writing teacher here in Los Angeles. The very first piece I wrote is now the beginning story in the book, “The Supermarket and a State of Grace.”

I came in and read that piece to the class. It felt scary and good to state my feelings, to see where I was, and then I didn’t write any poems about my son for maybe five years. Then I wrote “Over It,” which was published in Rattle. The next two poems were “Mahogany Funeral Urn” and “Snow Globe,” which were published in The MacGuffin. I was just starting to submit my work and the reception was encouraging. It showed me there was indeed an audience for these poems. The woman who finally ended up publishing the book, Clare MacQueen, said, “Look, if you ever want to publish these poems, I’m a publisher, send them to me.” I did. There were 12 poems when I gave her the manuscript, and I wrote a few more that ended up in the book and then I was done. It just kind of happened. It was never intended.

NG: Is there something important to you about sharing your experience?

CB: When Riley died, I felt lost in my grief and often alone. I felt that when I shared the poems, I was helping people like me. That is really what compelled me to get them published. It felt like it was something I had to do. I’ve had other moms contact me who have lost children and who read my book. I’ve become friends with many of them. That kind of connection, if it can provide any kind of comfort at all, that’s what it’s all about for me.

AF: So many people have reached out to me. It’s like a club of people who have lost children, from a stillborn child to someone in their 80’s who lost his 50-year-old son. I have received such gorgeous letters from people and phone calls from people who share that grief of losing a child. I think that was a hidden good part of writing the book, being able to reach out and make someone’s suffering a little more bearable.

NG: Do you think writing is healing?

CB: You know, I do think writing is healing. It doesn’t always feel like healing. Sometimes it feels painful. I recently wrote a poem about the night Riley died. I couldn’t have written it two years ago. It was so traumatic, but there’s something about looking at it from a distance and creating a poem or a piece of art. Creating something beautiful, that has meaning. It reframes the experience. There is also something about the editing process that seems to shift things, to be able to sit there and say, “Okay, what can I change about this? Let’s make it about the writing, not so much about how I feel, but let me find different words.” Keeping the emotional truth, but changing the words. Maybe it’s about control.

AF: People say, ‘I’m so glad you’re writing. It’s such a healing experience for you.’ Forgive me, but that’s bullshit. It’s tearing me apart. I just checked my calendar; I have 10 readings coming up, and reading these poems is just like opening myself up again and again and again. I think it’s a bleeding. Maybe there’s a bit of relief in bleeding all over the page, but no, I don’t think it’s healing at all. To give you a sense of perspective, I wrote and published over 100 poems during the same time period that I wrote the 14 poems that make up State of Grace. That’s to give you an idea what those 14 poems cost me in emotion and devastation. I’m a confessional poet and I write from my own life. For me to write, I’ve got to put myself there. If I don’t, I’m really not writing worth a damn.

NG: Can you talk a bit more about what it’s like to read your work?

CB: I remember reading some of these poems in class and just shaking and feeling really deranged. But what’s interesting is that once I’ve read that way, I can usually read them again. I am very connected to the poems, but it’s not as traumatic as reading them the first time.

AF: I am a trained actor; I worked professionally as an actor for many years, so I approach my readings as a professional actor would. I work on my poems; I work on my delivery. I’m able to separate the reader from me.

NG: I’m wondering if you have any favorite poems in your book?

CB: I definitely do. I’d say my top favorite is, “What Would Wislawa Szymborska Do?” I have moments with certain poems where I feel as though I didn’t write them. That was one of the poems that’s pretty much like the rough draft. It came to me one day when I was on a walk. I read it in class the next day, and that was the same day Szymborska died. It was so unreal. Another is “July 28th, 2012,” which won a contest that was judged by Ellen Bass. That was another poem where very little was changed from the original draft I wrote in my journal. Also “I Have 2x the Love for 1 Child,” about Desmond [Riley’s brother].

AF: Yes, there are some. I love the last poem in the book, “when her son is dead seven years.” That was one of the last poems written. I really like, “Dying Young.” It was written for my best friend Kate, who died in January of 2014 and was very close to my son, so I wrote that poem for both of them. Everyone seems to like “Death Warrant,” maybe because it’s so brutal.

NG: I understand the two of you do readings together.

CB: Yes, Alexis has been very inspiring to me. We look at each other’s work all the time. Whenever she writes a first draft of a poem she sends it to me; when I write a first draft of a poem I send it to her. She and I support each other. We did a reading called “Turning Grief into Art” at Beyond Baroque [a literary arts center in Venice, California] with Madeline Sharples, a writer who also lost a son.

AF: We met in Jack Grapes’s class. Chanel came in and announced her son died and wrote about it. My son had died a few years earlier. The last week of class I wrote a journal entry for class about what losing a son was going to be like for her and after I read it we decided to go out for lunch. Four hours later we were still sitting there, still talking. She wrote the foreword to my book, which I dedicated to my son and to her son.

POEMS FROM 'VANILLA MILK' AND 'STATE OF GRACE'

“I Have 2x the Love for 1 Child”

By Chanel Brenner

Since the death

of my older son,

I worry that the weight

of my love is too heavy.

I see my son hunched over,

carrying my grief

like a load of stones.

I worry he’ll learn

to bask in that love

till he sunburns,

come to crave

the sting and heat of it.

I worry that he is forming

like a rock in a river bed,

my grief-ridden love

rushing over him

like whitewater.

I worry that one day,

a woman will ask him

why her love is not enough,

and he won’t know

the answer.

Copyright2014, Chanel Brenner. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Chanel Brenner is the author of Vanilla Milk: A Memoir Told in Poems (Silver Birch Press, 2014), a finalist for the 2016 Independent Book Awards and honorable mention in the 2014 Eric Hoffer Awards. Her poems have appeared in Poet Lore, Rattle, Cultural Weekly, Muzzle Magazine, Diverse Voices Quarterly, and others. She is a contributor to All We Can Hold: poems on motherhood (Sage Hill Press, 2016). Her poem, “July 28th, 2012” won first prize in The Write Place At the Write Time’s contest, judged by Ellen Bass. In 2014, she was nominated for a Best of the Net award and a Pushcart Prize.

“Over It”

By Alexis Rhone Fancher

Now the splinter-sized dagger that jabs at my heart has

lodged itself in my aorta, I can’t worry it

anymore. I liked the pain, the

dig of remembering, the way, if I

moved the dagger just so, I could

see his face, jiggle the hilt and hear his voice

clearly, a kind of music played on my bones

and memory, complete with the hip-hop beat

of his defunct heart. Now what am I

supposed to do? I am dis-

inclined toward rehab. Prefer the steady

jab jab jab that reminds me I’m still

living. Two weeks after he died,

a friend asked if I was “over it.”

As if my son’s death was something to get

through, like the flu. Now it’s past

the five year slot. Maybe I’m okay that he isn’t anymore,

maybe not. These days,

I am an open wound. Cry easily.

Need an arm to lean on. You know what I want?

I want to ask my friend how her only daughter

is doing. And for one moment, I want her to tell me she’s

dead so I can ask my friend if she’s over it yet.

I really want to know.

© Alexis Rhone Fancher. First published in Rattle. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s poems can be found in Best American Poetry, 2016, Rattle, The MacGuffin, Slipstream, Rust + Moth, Hobart, Mead, Cleaver, and elsewhere. She’s the author of How I Lost My Virginity To Michael Cohen & other heart stab poems, and State of Grace: The Joshua Elegies. Since 2013 Alexis has been nominated for seven Pushcart Prizes and four Best of the Net Awards. She is poetry editor of Cultural Weekly.

References:

Bennett, Deb. “’I am Still a Mother’: A Hermeneutic Inquiry into Bereaved Motherhood.” Journal of the Motherhood Initiative 1.2 (2010) : 46-56. Print and on line.

Brenner, Chanel. Vanilla Milk: A Memoir Told in Poems. Los Angeles, CA: Silver Birch Press, 2014. Print.

Cixous, Helene. “The Laugh of the Medusa” (1976). JSTOR. Web. 20 July 2017.

Davidson, Deborah and Helena Stahls. “Maternal Grief: Creating an Environment For Dialogue.” Journal of the Motherhood Initiative 1.2 (2010) : 16-25. Print and on line.

Fancher, Alexis Rhone. State of Grace: The Joshua Elegies. Seattle, WA: KYSO Flash Press, 2015. Print.

Hendrick, Susan. “Carving Tomorrow from a Tombstone: Maternal Grief Followingthe Death of Daughter.” Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering 1.1 (1999) : 33-43. Print and on line.

Orr, Gregory. Poetry as Survival. Athens, GA: U of Georgia P, 2002. Print.

Ostriker, Alicia. Writing Like a Woman. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1983. Print.

Sharples, Madeline. Leaving the Hall Light On: A Mother’s Memoir of Living with Her Son’s Bipolar Disorder and Surviving His Suicide. Downers Grove, IL: Dream of Things, 2012. Print.

Steele, Cassie Premo. We Heal from Memory: Sexton, Lorde, Anzaldua and the Poetry of Witness. New York: Palgrave, 2000. Print.

Wagner, Shelley. The Andrew Poems. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech UP, 2009. Print.